'In Search of Immortality'

Keats, Proust, and Our Transcendence Over Time and Death Through Art

Had to do an essay related to a work in my Brit. Lit course…thought I’d share :D

There are two worlds, one the world of time, where necessity, illusion, suffering, change, decay, and death are the law; the other world of eternity, where there is freedom, beauty, and peace. Normal experience is in the world of time, but glimpses of the other world may be given in moments of contemplation or through accidents of involuntary memory. It is the function of art to develop these insights and to use them for the illumination of life in the world of time.

Marcel Proust1

English poet John Keats was a doctor by trade, so when he began coughing blood at age 24, he immediately knew what was wrong. “ ‘Bring me the candle, Brown,” he reportedly told his friend with great calmness, “and let me see this blood... I know the colour of that blood; it is arterial blood; —I cannot be deceived in that colour; that drop of blood is my death-warrant—I must die” (Brown, 1965). And tragically, he did. John Keats died in 1821 after a brutal struggle with tuberculosis: he was only twenty five. And yet, over two hundred years later people still know who John Keats is. We read him, discuss him, and in many ways he is more known now that he was in life. He lives on because of his art. Art, someone’s work, can in many ways transcend time and death itself as demonstrated in Keats’ famous poem Ode on a Grecian Urn as well as other literary works.

This theme of immortality through art is quite clear in Keats’ poem Ode on a Grecian Urn. The poem in the words of one article is a description of, “a work within a work of art” (Nersessian, 2021). Rather you see the poem as beautiful lovers or, as one author proposes, a rape about to happen (Nersessian, 2021), Keat’s poems freezes us in time:

Bold Lover, never, never canst thou kiss,

Though winning near the goal yet, do not grieve;

She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss,

For ever wilt thou love, and she be fair!

The article cited, argues that the poem is about a rapist and is told from his perspective. A compelling theory, but not what we are discussing. He does conclude with an interesting point, though, Keats’ Urn leaves us with a lot of questions. It is simply a moment, frozen in time, “It [the poem] gives him [Keats] a platform and waits, like the urn, to see how we will respond” (Nersessian, 2021). Keats’ Ode on a Grecian Urn is an interesting example of how a story, the art on the urn, can be frozen in time. How a moment, a memory, can be immortalized by a work of art.

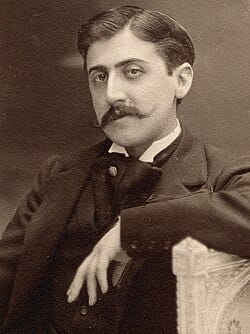

Unconventional French writer and socialite Marcel Proust died, young for his time, at the age of 51 in 1922 (Proust, Wikipedia.) After having spent the last several years of life almost completely confined to his bed, with some of the years before entirely cut off from the world, in his infamous cork-lined room, Proust, also, finds immorality in his art. The French existentialist philosopher and novelist Albert Camus went as far to declare that Proust’s monumental work, In Search of Lost Time, was a, “victory over the transitoriness of things and over death” (Camus, 1992.) As Proust and Keats demonstrate, and Camus supports, transcendence over time, and even death itself, can be attained through art.

Keats’ freezes time in Ode on a Grecian Urn by giving us one snapshot, one memory. One moment in time:

Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard

Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on;

Not to the sensual ear, but, more endear'd,

Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone:

Fair youth, beneath the trees, thou canst not leave

Thy song, nor ever can those trees be bare;

It is a moment of time that he can never know, that no one can ever know, because it is in the past. Keats’ can only guess, but in a way this poem becomes a work within, a work, within a work of art. Not only do we have the art on the urn immortalized, but we have the actual poem itself, the medium Keats’ uses, immortalized in time. This once again plays on concepts in In Search of Lost Time, where Proust uses, according to Helen Anderson, “the aesthetic device of arrested moments and recurrent sensation” (Anderson, 1982).

That also is the poem of reading a poem, viewing a portrait of a long dead writer, the work itself is an “arrested moment” of time. Our “dealing” with time is a genuine issue, Anderson argues, and is a way we confront our “hostile universe” to face the fragility, the insecurity, of our existence. Aldous Huxley, British writer and philosopher, writes in his essay The Doors of Perception (which details the time he took mescaline on the bequest of a psychologist friend), “The urge to escape from selfhood and the environment is in almost everyone almost all the time” (Huxley, 2009). Why? Is it because of this fragility, as Anderson mentions, our inability to deal with time? Is art the solution?

Keats’, it seems, found solace regarding the “personal time problem”, even in his other works, such as ‘When I have fears that I may cease to be,’ which details and organizes his fears of dying before he experiences love, this poem was written a couple of years before he became ill with tuberculosis. It is, in the words of one author, a work in which:

...the poet objectified his feelings and gave them profound expression in a form that we may recognize as our own. Not only did such technical work help organize Keats’ fears. It also answered them, in that to make a wonderful poem is to leave an object that may survive. When it became clear to him that he was dying, he wrote that ‘I think I shall be among the English Poets after my death’ (Birtwhistle, 2015.)

Keats’ works and personal writings showed an understanding of the conquering of a fear of death through art, or a legacy of any form. It is in seeing the works of your life that one can shed a fear of death. The end is simply a natural truth, a moment in time when you have reached the peak of the time allotted to you. This concept is also well illustrated by Proust’s narrator, in Finding Time Again, who nearing his death views his past and Time as a vast expanse he towers over, “I felt a sense of tiredness and fear at the thought that all this length of time had not only been uninterruptedly lived, thought, secreted by me, that it was my life, that it was myself, but also that I had to keep it attached to myself…I felt giddy at the sight of so many years below me.” Through his work, Proust writes that death is the end of Time. But, memory lives on, so we are not truly dead until, “the desire of a living body is no longer there to support them [memories].” Art, rather viewed or created, can become a tool to confront our own mortality.

Keats seems to recognize how the art of his urn transcends time in some of the closing lines, where he write of how time will waste a generation away, but how the, “marble men and maidens overwrought,/with forest branches and the trodden weed…shalt remain.” Proust seems to take this to another extreme, essentially sacrificing his mortal living life for the transcendence and lasting peace he finds in death and the immortality of his work. Proust, plagued by suffocating asthma, takes to his room where he pours out lightly fictionalized versions of the life he used to have. His writing is part philosophy, part story, and part deeply personal. Proust’s work is a sprawling novel dedicated to what he seemed to value above all else: the past and memory.

Proust’s maid, confidant, and rare friend Celeste reported that Proust was at peace with his death, refused medical care, and insisted on working on his book right until the end (Albaret, 2003). Was it his work that spared Proust from his fear of death? Maybe not dispelling the fear, but his work, as confirmed by his book, seemed to help him accept his death, “For myself, what I had to write was something different from a dying man’s farewell, longer, and for more than one person…No doubt my books, too, like my mortal being, would eventually die, one day. But one has to resign oneself to dying. One accepts the thought that in ten years oneself, in a hundred year’s one’s books, will not exist. Eternal duration is no more promised to books than it is to man.” (Proust, 2023).

As argued at the beginning, Keats’ works, and authors after him, seem to confront the “time problem” through art. They let go of their fear of death, by transcending above it. Though similar, both Keats’ and Proust’s solutions to the time problem were deeply personal. As Huxley writes, even though we live and act together as a collective society, “we are in all circumstances alone…The martyrs go hand in hand into the area, but they are crucified alone…By its very nature every embodied spirit is doomed to suffer and enjoy in solitude” (Huxley, 2009). Keats’ and Proust were “doomed to suffer” their illnesses and shortened lives alone. They had to confront time alone. And, even though we can witness this transcendence over time in their art, we must also face “the time problem” alone.

Keats’ poem Ode on a Grecian Urn is a beautiful example of how art can seemingly freeze time, shape reality, and help us confront the fragility of our own existence. Even though Keats died young, his works have left him immortalized the same way many others are still remembered today. All of us, whether a British doctor gone poet, a finicky French novelist, or those writing about them in the present day, must face the “problem of time.” We all, “doomed to suffer and enjoy in solitude,” must find our answers alone. For me, I find it in art, nature, Christ, and the vastness of the universe. Art is in many ways at the core of this though. Wheter it’s religious art, works about the universe, or the beauty of nature-art seems to be a common thread running through solutions to the time problem. What about you, dear reader? Where can you find immortality? What is your solution to the ‘problem’ of time?

Quoted in (Anderson, 1982).

Click here for References